Phuppu (our aunt) called me Thameh her derivative of Kamman ji, the nickname she had given me as a kid. My brother Shehzad was Shahji, Chantu Khan, or simply Chants. She also took great pride in announcing that whenever I bit her arm as a child, I would put a towel on it first, a practical example of my true love for her.

As kids in the 70s, my brother and I would spend Saturdays with Dadi and Phuppu. My earliest memories of Phuppu are being driven in their new car—a gift my uncle would send every couple of years. We would sometimes go to Malir to meet Tufail Saheb, a mystic who lived near a farm many miles away. At times, she drove us to our favourite fish and chips restaurant in PECHS where the meal would arrive on a small train or to Hill Park or to Play Land. At other times, she drove us to the barbers to get us a “Pathan cut”, Phuppo’s name for a drastic crew cut, which would leave my mother aghast.

She would make the most delicious food for us from Meerut, her maternal ancestral home, and would eat it with three fingers and her thumb with her pinky sticking out of her small hand. She would also eat and feed my grandmother “Khamira e Marvareed”, a semi-solid medicinal “Unani” concoction that she said was good for the brain and heart. It used to be locked in her green metal cupboard which had an oversized rotating handle on it. I would sneak a bit of the super sweet, brown, and gold speckled potion for myself whenever I could.

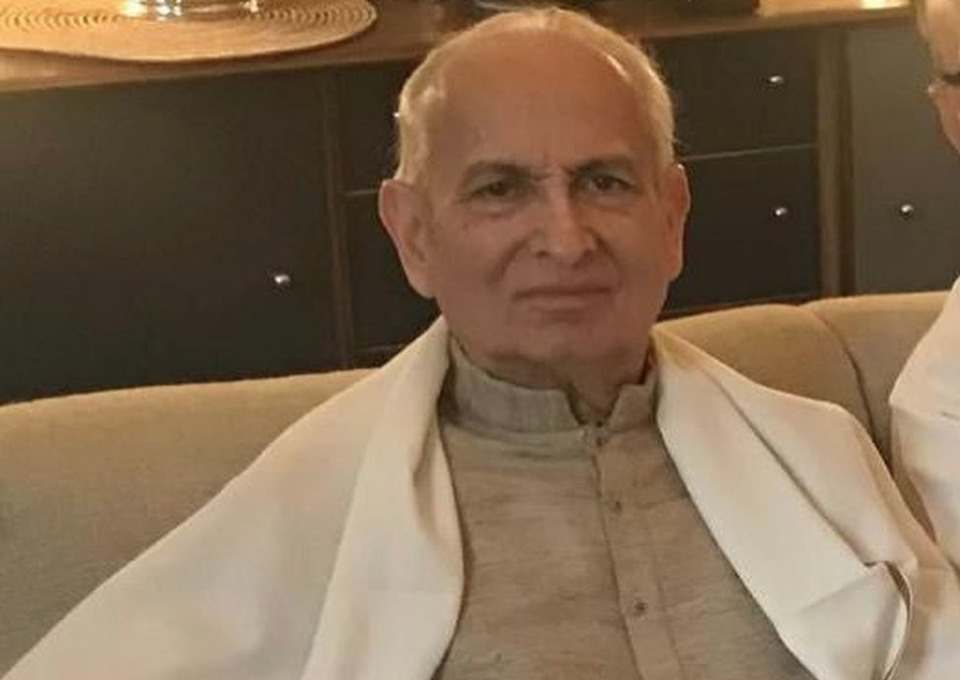

She would wear oversized dark glasses and in winter a kurta shalwar made of a material she called “Falalain”, which I suppose came from Flannel. I remember sitting in the back seat of the car glancing at Phuppo’s profile with her diamond nose ring glistening on her sharp, small nose.

Her journey and that of her two siblings and mother had been a long and bumpy one. In September 1949, mother and daughter along with my father (the youngest of the three siblings) arrived at the Karachi port aboard the Bhadrawati, a vessel that had left Bombay a few days earlier. My uncle Ikram had just landed a job at HBL in Bombay and had initially stayed behind.

This was their second abrupt dislocation. In 1934, the siblings suddenly lost their father and the family left Duelghat abruptly and resettled in Hyderabad Deccan. The charm of the fort she was born in or the Mango Orchards she played at had evaporated overnight and legal battles ensued. This impacted her deeply and shaped many aspects of her personality. And then there was Pakistan.

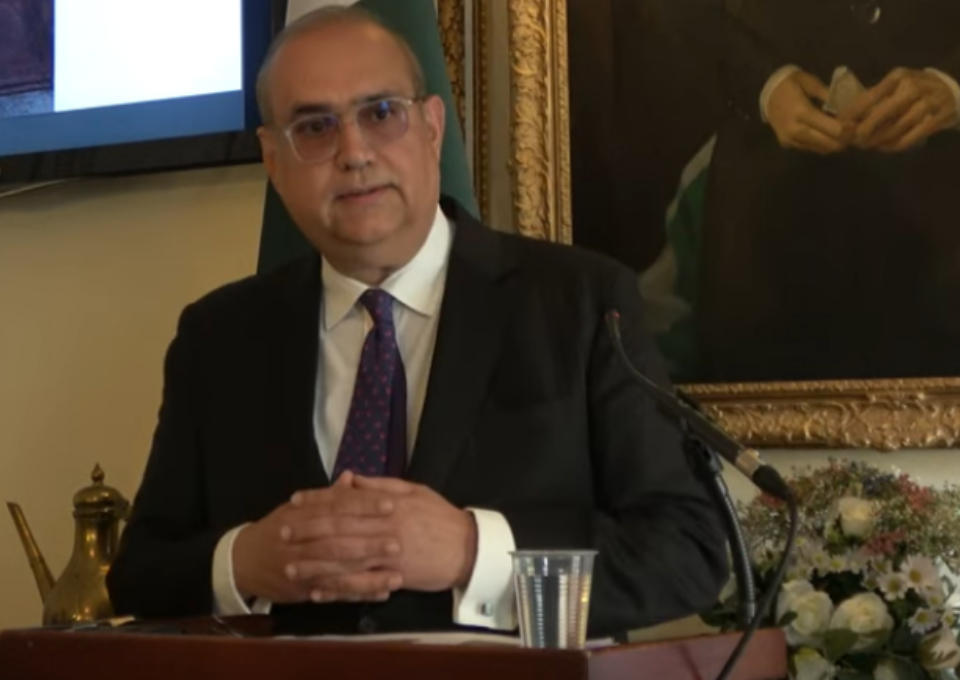

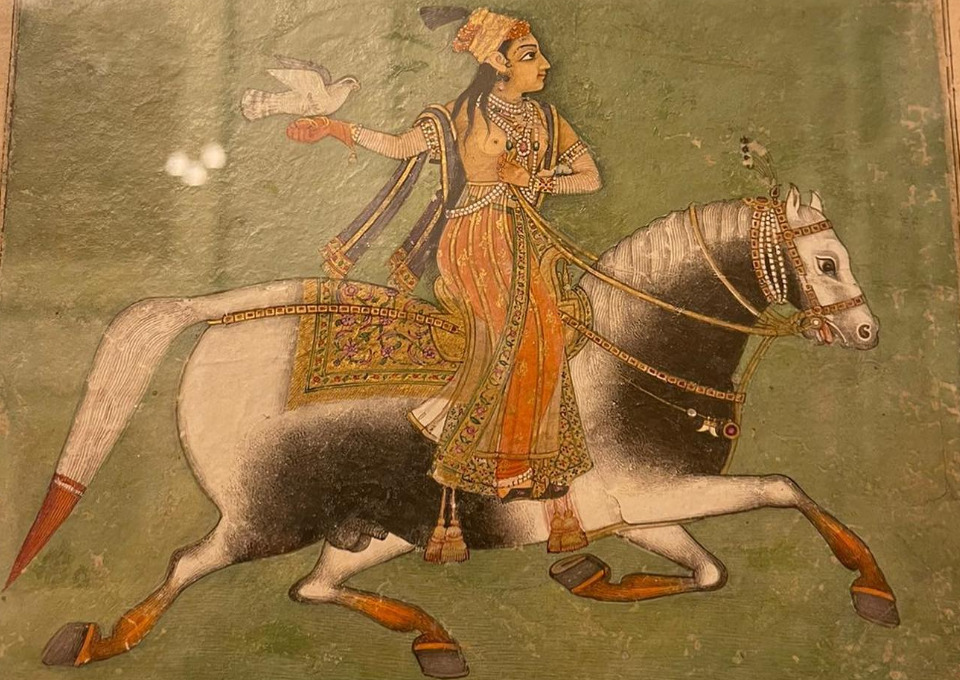

Within just a few years of disembarking the Bhadrawati, Dadi, and Phuppo established themselves as successful businesswomen with their sheer grit and determination. My dadi as the leader looking after design and production at Al Azmath Industries, a textile and handicrafts concern that employed destitute women initially in the verandah of Urooj, the home they had built. Phuppu was at the helm of sales, marketing, and procurement, a single woman in a new country bravely setting up shop, first at the Metropole hotel and then at the Karachi Port to sell their goods to tourists and sailors. And success came in spades. “When there was no room in the bags brimming with cash, they had to stuff money in pillowcases to deposit in a bank”, my mother recalls.

In the 50s and 60s, the business venture also took the duo across the world from Japan to Canada, Londön, Italy, and France. Her rugged and determined manner and, my dadi’s calm, reflective, and brilliant mind laid the foundation for the success of my whole family. My father and uncle were sent to some of the best universities in the world, while Phuppu did courses in textile design at Sorbonne in Paris and at Osaka University.

Traditional gender roles were totally reversed in my family. It is the women who financially supported the men at the most important time of their educational and professional growth. And that too in the 50s. She never wore that success on her sleeve neither had any airs of the contributions the mother and daughter had made for the sons. She took it in her stride.

Phuppu was unfiltered, unimpressed, unassuming, firey, and impossible. She was also deeply loving, concerned, spiritual, and charitable. She looked at Bhayya, her elder brother as a father figure and treated my father, Baba, as a kid even when he was 80. For decades, she sent funds to the mausoleum of Khwajah Moinuddin Chishty in Ajmer, fed orphans, and looked after the destitute. She also regularly disturbed any events she deemed to be snobbish and brazenly took on people who she believed had wronged her, whether they had or not.

She was also sensitive. Once when she called me in the middle of the work day many years ago, I said “Phuppo I will call you back, I am really busy”. I forgot to call her back. A few days later when I saw her at a family wedding and went to hug her, dismissing me with her arm she said “I am very busy. I will call you back” She then warmly hugged me back anyway.

Phuppu, thank you for the many hugs and shouts and for all that you did for us. Sleep well and peacefully now, forgive me for not being more attentive, and give the angels a break. Every now and then.